Lupine Publishders | Journal Of Surgery & Case Studies

Background

Symptomatic mesenteric ischaemia is an uncommon disease entity which

can prove complicated to diagnose and manage. Both

endovascular and open operative approaches have been described but the

nutritional complications caused by poor gut absorption

can mean that these patients may be at higher risk of operative

complications, and appropriate care should be given to preoperative

nutritional optimisation prior to surgical management.

Keywords: Critical Mesenteric Ischaemia; Iron Supplementation; Preoperative Optimisation

Chronic mesenteric ischaemia (CMI) caused by atherosclerotic

stenosis of the arteries supplying the small bowel is a fairly

common finding at autopsy (reported to be between 12-60% of

elderly patients at autopsy [1]), however symptomatic critical

mesenteric ischaemia is rarely reported and can elude diagnosis

for extended periods of time due to the non-specific symptoms of

presentation. Patients may complain of post-prandial abdominal

pain, appetite and weight loss, and “food fear” [2]. In these patients,

as the disease process can be protracted and well-established by

time of diagnosis and management, patients may show signs of

long-term undernourishment, including weight loss, electrolyte

and micronutrient deficiencies and declining overall health [3]. As

such, substantial preoperative optimisation may be required prior

to consideration of operative management and revascularisation.

Consideration should also be given postoperatively to a possibility

of re-feeding syndrome. We present here the case of a 70-yearold

woman seen in our unit with a complex critical mesenteric

ischaemia compounded with general frailty and undernourishment.

A 70-year-old woman was initially referred by her primary care

doctor for assessment of unintentional weight loss for investigation

of possible malignancy. At time of referral, the patient had lost 9

kilograms (from 51kg to 42kg) within 4 months (body mass index

18) and complained of persistent nausea and upper abdominal

pain. She was noted to have a background of rheumatoid arthritis

and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A CT scan of the thorax,

abdomen and pelvis did not show any sign of malignant lesions, and

upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed only mild gastritis. The

patient was treated with helicobacter pylori eradication therapy

and discharged (Figure 1). She was re-referred to the service

following further concerning weight loss to a body weight of 35kg

with a BMI of 12.86. A repeat upper GI endoscopy was completely

normal. Blood tests showed a mild red cell macrocytosis (MCV 100)

and low ferritin levels; renal function, electrolytes and liver function

tests were unremarkable. Further review of CT imaging revealed an

occluded coeliac trunk with stenosis at the origin of the superior

mesenteric artery and suspicion of post-stenotic aneurysm.

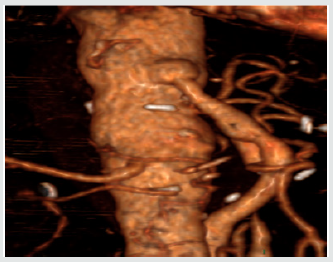

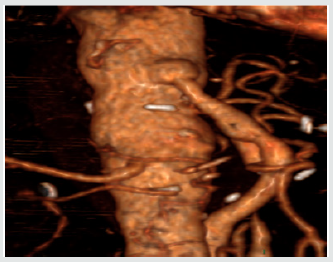

The patient underwent CT angiography which showed critical stenosis with short occlusion of the coeliac trunk origin, and a 3cm occlusion at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. Bowel was entirely supplied by collateral vessels originating from the inferior mesenteric artery, which was itself also stenosed at its origin. Abdominal aorta, renal arteries and iliac vessels did not show any significant disease. Attempts were made to treat the stenoses with an endovascular approach but were ultimately unsuccessful as it was not possible to identify mesenteric vessel origins due to severity of stenosis. Following this the patient was planned to undergo supracoeliac aortic-SMA bypass, with preoperative optimisation with IV iron supplementation. The patient’s low ferritin levels at diagnosis were supplemented by this approach and came up to normal levels by the time of procedure; this was reflected in the improved full blood count of the patient.” The patient underwent laparotomy and adhesiolysis, following which the root of the SMA was identified (Figures 2 & 3).

ACritical mesenteric ischaemia poses a particular challenge for

preoperative optimization; reduced arterial supply of the small

bowel is likely to affect its function and the degree to which this

occurs is likely to depend on the severity of the stenotic areas.

Equally, preoperative anaemia is known to increase the risk of blood

transfusion, and in turn, increase the morbidity and mortality risk

of undergoing a procedure [4]. A recent study involving patients

with colorectal cancer treated with preoperative intravenous

iron supplementation showed that the haemoglobin level was

significantly increased in the active treatment group, however

the further impact of this increase on risk levels of morbidity

and mortality is not known [5]. In particular, the effectiveness of

this intervention is unknown in patients undergoing high risk

aortic surgery. A 2015 Cochrane report identified 3 prospective

randomised controlled trials investigating its use – two in colorectal

surgery and one gynaecological study. This review suggested that

there was a reduction in use of blood transfusions associated with

preoperative intravenous iron supplementation but it was not

statistically significant. Each of these studies had small patient

numbers, however, and overall the authors note that the studies

are unlikely to have had sufficient power to reliably analyse the

significance of the effect [6].

We present a case of critical mesenteric ischaemia with use

of preoperative intravenous iron supplementation. Intravenous

iron replacement therapy has been noted in the literature to have

reduced the prevalence of preoperative anaemia, though more

studies are needed to see if this truly translates to lower levels of

operative morbidity and mortality, and if this effect is seen across

differing surgical procedures.

Abstract

Background

Symptomatic mesenteric ischaemia is an uncommon disease entity which

can prove complicated to diagnose and manage. Both

endovascular and open operative approaches have been described but the

nutritional complications caused by poor gut absorption

can mean that these patients may be at higher risk of operative

complications, and appropriate care should be given to preoperative

nutritional optimisation prior to surgical management.

Objective

We present a case of critical mesenteric arterial stenosis treated with preoperative intravenous iron supplementation to illustrate preoperative optimisation and therapeutic approaches, together with a selected review of the literature

Conclusion

Preoperative parenteral iron supplementation is likely to be effective in reducing preoperative anaemia but the impact of this intervention on postoperative blood transfusion and other complications in the context of complex aortic surgery is unknown.Keywords: Critical Mesenteric Ischaemia; Iron Supplementation; Preoperative Optimisation

Introduction

Case Report

The patient underwent CT angiography which showed critical stenosis with short occlusion of the coeliac trunk origin, and a 3cm occlusion at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. Bowel was entirely supplied by collateral vessels originating from the inferior mesenteric artery, which was itself also stenosed at its origin. Abdominal aorta, renal arteries and iliac vessels did not show any significant disease. Attempts were made to treat the stenoses with an endovascular approach but were ultimately unsuccessful as it was not possible to identify mesenteric vessel origins due to severity of stenosis. Following this the patient was planned to undergo supracoeliac aortic-SMA bypass, with preoperative optimisation with IV iron supplementation. The patient’s low ferritin levels at diagnosis were supplemented by this approach and came up to normal levels by the time of procedure; this was reflected in the improved full blood count of the patient.” The patient underwent laparotomy and adhesiolysis, following which the root of the SMA was identified (Figures 2 & 3).

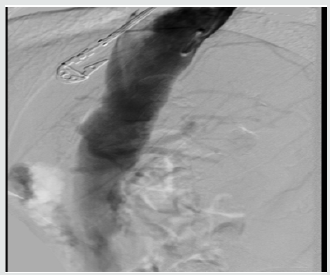

Figure 5: Postoperative CT with 3D reconstruction

showing right renal artery takeoff and vein graft.

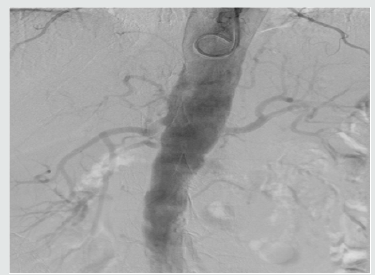

A long saphenous vein graft was harvested and anastamosed to

the supracoeliac aorta proximally and the terminal SMA distally. On

completion of anastamosis and upon opening of the graft, the small

bowel became flushed pink and began enthusiastically peristalsing

almost immediately (Figures 4 & 5). Postoperatively the patient

progressed well, and upon follow up, had gained 7kg in the space

of 3 months. Symptoms of post-prandial pain and nausea, as well

as appetite generally, had improved significantly from her previous

morbid state.

Discussion

Conclusion

For more Lupine Publishers Open Access Journals Please visit our website:

http://www.lupinepublishers.us/

For more Surgery Journal articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/surgery-case-studies-journal/

http://www.lupinepublishers.us/

For more Surgery Journal articles Please Click Here:

https://lupinepublishers.com/surgery-case-studies-journal/

To Know More About Open Access Publishers Please Click on Lupine Publishers

No comments:

Post a Comment